الرَّحْمة

root: ر-ح-م / noun / definition: mercy

I can summarise my PhD progress today by saying that I eventually won the wrestle with page numbers on my running thesis draft.

Of course the developers had to make that difficult, because God forbid someone would want the numbering to start on page 3 rather than page 2, as I’d had it before.

(Here’s an idea: why doesn’t Word just ask me on what page I’d like the numbering to begin?!)

But, at some indistinct point after creating a page break and (shortly) before having a breakdown, I’d managed it. الحمد لله.

And at another recent but indistinct point in time, my mind flew back to a comment left a while ago on my post Some Arabic-Akkadian Lexical Observations:

What Kieran (whose comment I forgot I hadn’t replied to, sorry!) was referring to was the last item on my list of some Arabic-Akkadian lexical similarities:

rē’ût: shepherdship (perhaps a bit of an odd one to end this list with, but I couldn’t help noticing the Arabic link when I heard this one in class; the Akkadian suffix –ut forms the abstract noun (like the Arabic ـيّة), what’s left is the equivalent of the Arabic root ر-ع-ي (r-‘-y), which is related to shepherds, tending animals, etc.)

And Kieran was right: Arabic has retained an ـوت suffix on some abstract words. Look at these:

- جَبَروت = power, tyranny

- مَلَكوت = realm, sovereignty

- ناسوت = human nature, mankind

- لاهوت = deity, divinity

- كَهَنوت = priesthood

- رَحَموت = mercy

This last word, رحموت, is what inspired this post.

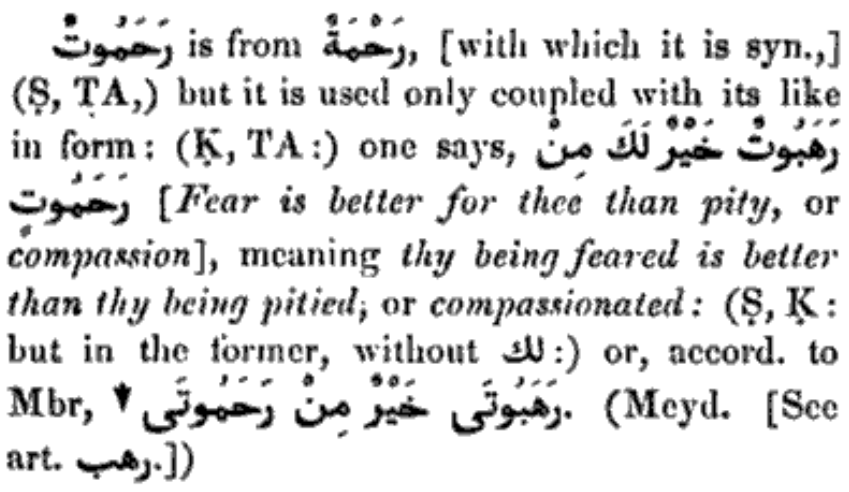

You see, I was looking in Lane’s Lexicon, when I saw its entry on page 1057:

It states that رحموت is derived from—and synonymous with—رَحمة.

But also that رحموت only appears alongside other words of the same form, i.e. with the ـوت suffix.

And it gives us an example:

رَهَبوت خيرٌ لك مِن رَحَموت

being feared is better for you than being pitied

(literally: fear is better for you than compassion)

That in itself is something to mull over.

But also, how strong is the connection between the Arabic and Akkadian –ūt suffixes? And why is it that Arabic words with this suffix are used in limited contexts? Has this changed over time?

I also couldn’t help but notice that رحموت sounds like the colloquial رح اموت (“I’m going to die”)… it’s an inconsequential observation, but an observation nonetheless.

Does anyone know more about this suffix and its uses in either Arabic or Akkadian? If so, let us all know in the comments below!

See you soon.

.في أمان الله

If you’d like to receive email notifications whenever a new post is published on The Arabic Pages, enter your email below and click “Subscribe”:

I found out that these words are on the scale of فَعَلوت which is one of the scales of the صيغة المبالغة which refers to something being abundant. For example رحموت gives the meaning of واسع الرحمة ‘abundant mercy’. It’s interesting to see the semantic aspect of a word when it’s on different scales. Thanks for posting something beneficial like this!

Interesting, thanks for sharing this! 😄

Hey, thanks for the follow-up! It got me curious again, so I looked up the -ūt suffix in Carl Brockelmanns Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der semitischen Sprachen and all I wanted to know was right there on pages 414 and 415 (translated by GPT):

Since the book came out in 1908, Hebrew has been revived and the -ut suffix became extremely productive and is used to form abstract nouns such as ofkiyut “horizontality” (from ofek cf. Arabic ʾufuq) or magnetiut “magnetism”.

Wow, thanks so much Kieran for sharing more of your insights! This is like a post in itself 😮